Student D: Bright or Gifted? How you can tell and why it matters…

A bright spark….how does the EAL team provide evidence that a new EAL child is gifted?

Student D came from an educated background in her home country. She did not speak English but had been taught it at school. ‘D’ could read and write simple English, although not much, but seemed observant and quick on the uptake. Was she simply well-educated? Or was she gifted?

Previously educated pupils often come across as very bright. But how can you tell if one should be treated as a Most Able Student (MAS)? Why does it matter whether they are labelled MAS or not?

What information was needed to evaluate ‘D’? More importantly, what evidence could we produce that would convince teachers to treat her as MAS?

I will look at each question in turn, including discussing how hypothesis testing fits a non-SEN case. But first, we will look at the history of the Most Able Student category and school responsibilities.

At this point, three related issues arise. One, if a child doesn’t speak English well enough to reveal their cognitive ability, how does the EAL team determine quickly whether an EAL child is well above cognitive average? Two, how can the EAL team provide enough support to gain the EAL child access to MAS teaching and opportunities once they are accepted as MAS? Three, is the school actually providing appropriate challenge for their Most Able students?

Able, Gifted and Talented to Most Able Pupils

In 2006, the Department of Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), required that schools keep a centralised register of Able, Gifted and Talented (AGT) pupils. ‘Able and Gifted’ meant academically; ‘talented’ covered arts, languages and sports, and took into account interests the child pursued independently and to a high level. The idea was to encourage these interests and provide an in-school outlet for such enrichment opportunities as well as negotiate schoolwork in a way that flexibly supported the child’s endeavours (such as child acting, junior scouted footballers, performing musicians). Note: AGT has now been replaced by the term Most Able Student (MAS).

The DCSF defined AGT as “Children and young people with one or more abilities developed to a level significantly ahead of their year group (or with the potential to develop those abilities).” (DCSF, 2008)

Schools were to keep a register, defined as below, to feed into a National Register.

The National Register – first announced in the 2005 White Paper ‘Higher Standards: Better Schools for All’ – is an amalgamation of all maintained schools’ gifted and talented registers (submitted through School Census returns) and Key Stage results.

Interestingly, it was to feed into a nationally kept register of the ‘gifted and talented population’ of school-aged children in the UK. Most importantly, children who were AGT and underachieving were to be identified and targeted for action by schools. (DSCF, 2008)

The report listed possible identifiers in a ‘General characteristics of gifted and talented learners’ tick list, saying that ‘while the following characteristics…are not necessarily proof of high ability….they may alert teachers to the need to enquire further into an individual’s learning patterns and ability levels’. The child in question might:

be a good reader;

be very articulate or verbally fluent for their age;

give quick verbal responses (which can appear cheeky);

have a wide general knowledge;

learn quickly;

be interested in topics which one might associate with an older child;

communicate well with adults – often better than with their peer group;

have a range of interests, some of which are almost obsessions;

show unusual and original responses to problem-solving activities;

prefer verbal to written activities;

be logical;

be self-taught in his/her own interest areas;

have an ability to work things out in his/her head very quickly;

have a good memory that s/he can access easily;

be artistic;

be musical;

excel at sport;

have strong views and opinions;

have a lively and original imagination/sense of humour;

be very sensitive and aware;

focus on his/her own interests rather than on what is being taught;

be socially adept;

appear arrogant or socially inept;

be easily bored by what they perceive as routine tasks;

show a strong sense of leadership; and/or not necessarily appear to be well-behaved or well liked by others.

Conversely, Gifted and Talented underachievers may tend to:

have low self-esteem;

be confused about their development and about why they are behaving as they are;

manipulate their environment to make themselves feel better;

tend towards a superior attitude to those around them;

find inadequacy in others, in things, in systems, to excuse their own behaviours.

It continued that ‘frustration and disaffection’ were dangers to be avoided for AGT pupils, including those with a disability or difficulty. As such, developing strategies and approaches to countering underachievement should be an integral part of the school policy for gifted and talented provision.

The DCSF also suggested a raft of methods for identifying such pupils, saying ‘Schools have the discretion to decide how best to identify their gifted and talented pupils but are likely to obtain the best results by drawing on a wide range of information sources, including both qualitative and quantitative information’. A range of popular methods for identification were listed as below:

1 Teacher/staff nomination

2 Checklists

3 Testing achievement, potential and curriculum ability

4 Assessment of children’s work

5 Peer nomination

6 Parental information

7 Discussions with children/young people

8 Using community resources

One can see from the mixed data approach, that the original guidelines presented ample opportunities to offer qualitative evidence of EAL cognitive ability. Most EAL professionals could get an EAL child on the register by evidencing arts, language or sports talents. However, being able to offer evidence of highly verbal, opinionated, widely knowledge, logical or obsessionally interested traits would take a first-language interview and observational data of an experienced EAL practitioner. Thus a hypothesis-testing approach would be necessary.

…being able to offer evidence of highly verbal, opinionated, widely knowledge or logical traits would take a first-language interview and observational data of an experienced EAL practitioner…

Using hypothesis testing

I have previously discussed the rationale and research behind hypothesis testing in my two previous case studies on EAL and SEN. (Practical Case Study 1 and Practical Case Study 2).

Frederickson and Cline (1991) suggest a comprehensive framework of information gathering when assessing whether an EAL student is experiencing curriculum difficulties due to cognitive deficiency or to a need for linguistic and socio-cultural adjustment. These are a part of a ‘hypothesis-testing approach’ (Frederickson and Cline 1991, Hall 2001) where possible variables contributing to the educational difficulty are considered and eliminated as part of the assessment of possible SEN in an EAL child. These are also useful in the case of an AGT or Most Able EAL student.

These include:

- Background: gaining a full picture of the child’s previous educational experience;

- Language: conducting a first-language assessment to ascertain whether the child is working at or above an age-appropriate level in their own language;

- Communication Skills: observations of pupil interaction in classroom and play contexts, as well as gathering observational information from community language or religious schools as part of a multi-cultural approach;

- Differentiation: checking that appropriate classroom provision for EAL language learning need is effectively used;

- Affective Filters: investigating emotional and psychological factors affecting achievement such as past trauma, racist bullying or other environmental stresses; (Frederickson and Cline 1991, Pim 2010)

- Testing: considering raw data on national standardised tests but as a minimal part of the whole picture.

Note: standardised tests usually have no construct validity for EAL pupils, i.e., they do not measure what they are designed to test in pupils who do not understand the test instructions or questions, and therefore are not a good source of evidence to confirm or deny a hypothesis of cognitive ability.

Frederickson and Cline (1991) stress that only after these questions are explored in turn should the hypothesis that a learning or language disorder be considered. However, the same process applies for a potentially Most Able EAL pupil and it begins with the background interview.

- Background: Bilingual Interview use – a bilingual interview should get info on:

- previous schooling experience and any gaps in schooling / when school started

- (some school systems start at 7 years old – this does not constitute a ‘gap’ in schooling)

- with who the child is here and some experience of how they came

- what languages they speak and with whom they speak them

- preferred subjects or school experiences

- medical needs / allergies / glasses / hearing or eye test ever taken

- religious practices including main holiday and food needs

- ambitions – what do they want to do in the future?

When Student D was interviewed, it was clear that she had great ambitions. Both her and her family said that they had moved to the UK for access to the world’s top universities. Indeed, she stated that she wanted to go to university at Oxford for Business. However, again, having great ambitions and the ability to fulfil them are separate things. How could we assess her cognitive profile? Her background interview also revealed that she had full previous education, could read and write music and play two instruments.

In terms of the UK school system, her ability to read and play music, could itself qualify her to be put on a talented list, if the school kept one. It is important to find out about the EAL students’ art, drama, music and sporting abilities and proficiencies. Most schools will have a variety of extra-curricular opportunities lined up for talented pupils, from local and countywide sports fixtures to art museum visits or creative collaboration with local professionals. This is part of the reason to get your gifted EAL kids on those lists. Life experiences build language and confidence!

2. Language: conducting a first-language assessment to ascertain whether the child is working at or above an age-appropriate level in their own language.

Many schools do not have access to home language speakers. However, this is where a register of language abilities in staff and any 6th formers helps. The child should be asked a range of questions, either verbal or written, which allow for complex language, including: observed comparisons between home country and UK education systems; preferences and thoroughly reasoned justifications; the ability to use whatever previous knowledge they have to flexibly describe a current aspect of their UK life for which they do not yet have native terminology. This is much easier with a native speaker available.

3. Communication Skills: observations of pupil interaction in classroom and play contexts, as well as gathering observational information from community language or religious schools as part of a multi-cultural approach.

Observe them as they speak: either in the home language or English. Are they looking around trying to find something in the room they can use to help them communicate a point to you? Do they seem to understand that you are also limited in your knowledge of what they are describing (when describing home)? Gifted students may show great empathy and may try to fit their language to your level of understanding. Do they use actions, facial expressions, hand gestures….anything they have at their disposal to help you understand their point? This will often be the case with gifted, previously educated students.

Less verbal, but just as gifted

Of course, it is also the case that EAL students may be gifted but less verbal, more mathematically or pictorially oriented. In this case, it is best to ascertain what the student might be interested in (theory of relativity, history, architecture, calligraphy, higher maths). Have on hand a variety of high-level textbooks or coffee table books with good pictures: biology, fossils, architecture, history, art, graphic arts, sculpture and paintings, Fibonacci spirals, cars…whatever you can get your hands on. A visual dictionary is useful. See what interests the student enough to talk about it with you at length. This will require a native speaker unless you can get the student to show you their interest and perhaps to do an equation, drawing, etc.

Gifted, but NOT previously educated

This is tricky because gaining recognition as gifted in an educational setting presupposes transferable curriculum knowledge that the UK system will recognise and value. Often, bright children from uneducated backgrounds cannot prove on ‘our terms’ that they are gifted. Example: Two Somali brothers (Year 8 and 9), who both had 1-2 years of education before a traumatic immigration journey, were being shown pictures as we were searching for communicative material. When he spotted a rooster/cockerel, the younger Abdi got very excited and said pointing, ‘Man!’ ‘Chicken!’ We knew he was trying to say ‘male chicken’ and it was clear he was knowledgeable and desperate to communicate it!

An untrained brain is not the same as low cognition, although it they may present in a similar fashion. Watching a 6’2’’ Somali 15-year-old try to learn the three times table on his fingers looks like mild learning difficulty (MLD). It is not. It is lack of training in remembering and holding facts and sequences. Continue to search for interests and proficiencies in these children where they are at their best and can communicate talents and ability.

4. Differentiation: checking that appropriate classroom provision for EAL language learning need is effectively used.

Student D went directly into GCSE Economics and Business Studies. Her teachers were concerned that she simply would not get the concepts and language. I asked them to persevere and to give her a vocabulary list for the subject. She translated the entire list of terms in two evenings and began attempting to use the key words in English within Italian sentences! This is a hallmark of Most Able, previously educated EAL pupils. They take the initiative with their language learning and put in the extra work. They often take very little time to catch up to peers due to their incredible work ethic. Again, not all Most Able pupils are quite so bookish—context and background plus disposition will help you to decide.

5. Affective Filters: investigating emotional and psychological factors affecting achievement such as past trauma, racist bullying or other environmental stresses.

Home sickness, being overwhelming and exhausted by English-Language submersion, missing friends, doubting one’s abilities: these are things that interfere with children being able to show their true cognitive ability. I am currently working with a Czech Year 10, new to the country whose academic confidence came from his Maths ability. Not understanding the Maths curriculum in the UK has shaken him. Reasoning questions are mostly literacy-based and very reliant on prepositions, which change for every language and often do not translate. He looks exhausted and retreats to his PS4 in the evenings where he can communicate with his home country friends. His family described him as very bright—the top of his class with top grades—he shows little of that at the moment.

This can often be the case. Such children will need time to adjust, a lot of understanding and a chance to speak/read in their home language during the week for a ‘brain break’. Withdrawal EAL provision or ESOL class, where English language can be slowed down and attached to pictures will help tremendously, even if it is once a week. Whether they are Most Able is a question that will need to wait until they have settled.

6. Testing: considering raw data on national standardised tests but as a minimal part of the whole picture.

This is simply not appropriate at this language acquisition stage and does not help ascertain cognitive ability. If you are told that a Most Able referral needs data as evidence, point out the construct validity difficulties of using standardised testing and the range of accepted evidence types cited by the DSCF, which is still the current model under the DFE.

Measuring Progress and Final Considerations

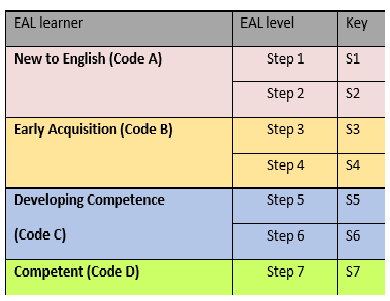

Without a doubt, EAL pupils make progress in their English language acquisition at differing rates. The new Department of Education Competency Codes and Steps provide much larger chunks of language learning and make measuring smaller gains difficult. To help measure progress formatively, schools may choose to break down each Step into three micro-levels such as Step 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3. The .1 may be ‘just acquiring’ a skill, .2 is ‘more confident’ and .3 is ‘secure’ and ready to move onto Step 2.

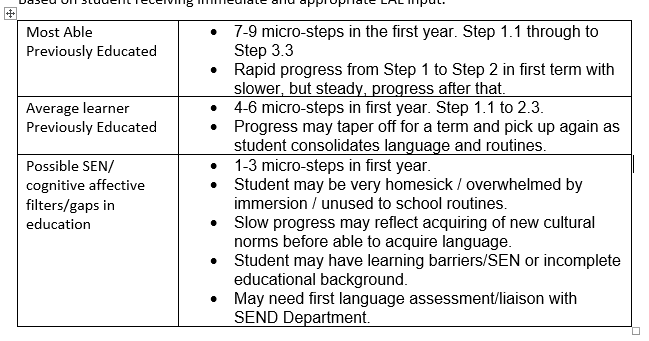

I have found from my experience on the new DFE Scale of Competency that a MA student who is previously educated will make lightening progress from A1 to B4 within 2-3 terms, and be on the verge of a C5 in a year. This will be much faster than an average or even above average ‘bright’ student. I have put together the below table based on the last three years’ experience against the new framework.

Expected Progress Guide

Based on student receiving immediate and appropriate EAL input.

This should help you give some appropriate attainment data to support any other qualitative evidence you have compiled. It matters whether an EAL student is identified as MAS for the same reason it is important that any other student is identified. Most Able students need a range of opportunities to develop their very good potential and to support their high aspirations. It will be up to you to advocate for them in your institutional setting.

Student ‘D’ has been at our school for 15 months and is already in the top 25% of all her GCSE classes. She is still learning some of the more complex aspects of English, like prepositions, but is currently testing at C6/D7. This means that in 4 terms of learning she has progressed from A1.3 to C6.3 equalling 15 micro-levels. In comparison, most average children would make a third of that progress. The school is still developing its MAS programme, but at least she will have access to it as it develops.

Most EAL families and their children have made unimaginable sacrifices to be educated in the UK. It is our moral duty to ensure those sacrifices, often made by the entire family, have been worthwhile and that another potential doctor, software designer, inventor, athlete, composer, artist is allowed to contribute their unique talents to humanity.